Her mother née Barbara Argoutinsky-Dolgoroukov was born on the vast family estate near Odessa. Her father, Prince Alexander Argountinsky-Dolgoroukov, a retired general, raised his children according to Tolstoy’s precepts, refusing the role of courtier in order to create social reforms on his property. Despite the numerous servants on the estate, his children made their own beds and tidied their rooms. He employed one of Tolstoy’s disciples as tutor for his son David. Barbara was an excellent musician, pupil of a pupil of Beethoven. At the age of eighteen, she married her first husband, Baron von Erlenvein, the son of the physician to King Ludwig of Bavaria. The newlyweds went to live in Bessarabia where her daughters Maniounia and Nina were born. During a pogrom, she hid Jewish families in their home and hung white curtains on the windows to signify that they were a Christian family. She divorced her husband after Nina died of meningitis.

She went with Maniounia to live in Tiflis at her grandmother Ninotchka’s home, where she met and soon married Helene’s father, Christopher Avakoumovitch Wermiceff, born in Baku. A dynamic agronomist whose father had sold his oil fields to the Nobel brothers, Wermicheff became their manager in Russia. The Wermicheffs had five children: Grisha, Helene, Vanya, Barbara and Kotik.

1898 HP born in Tiflis 30 April or 17 May (old or new calendars)

1903 Family moves to St Petersburg where father, Christophor Avaloumovitch Wermicheff is manager for Nobel oil interests in the Caucasus.

1904 Family returns to Tiflis, but father does not live with the family. Beloved half-sister Mania (aka Maniounia) has married Sasha Moët.

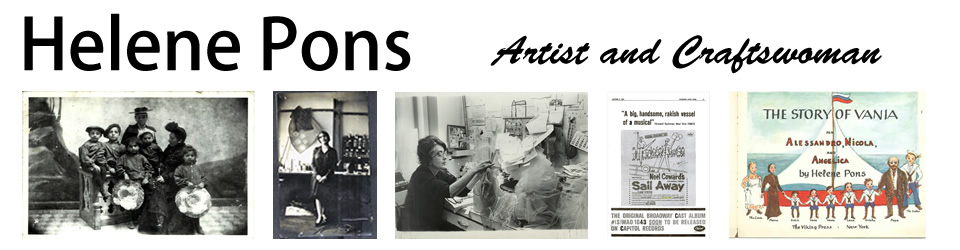

1905-1907. Fearing disorders during the 1905 revolution, Wermicheff sent his family to Switzerand. Helene is the sad-looking little girl in the center of the photo taken at the railroad station in Vienna on their way to Switzerland. Helene later said she felt she had to look very serious.

1908 Tiflis. Barbara opened arts and crafts school where Helene was the star pupil.

1909 Typhus epidemic in Tiflis. Helene was relegated to a public quarantine. Her mother forbade the nurses to shave her head.

1912 Helene develops pleurisy and slight TB. Mother sends other children to Baku to live with their father and his two sisters. Father publishes most important newspaper in the Caucasus Baku. Mother sets off for Italy with Helene, but on the train encounters a doctor who tells her to take the sick child to a sanatorium in Leysin in Switzerland.

1913 Helene contracted TB. Mother accompanied her to a sanatorium in Leysin (Switzerland) where she spent three years, while her brothers and sister went to live with her father in Baku. She became engaged to terminally ill Pierre Boudé from Montauban in France, who left her a small legacy.

1917 Helene returned to Russia, in the full throes of the October Revolution. Her father met her at St Petersburg and told he could no longer support her: she must fare for herself. He had divorced Barbara, remarried and now had two children. He went back to Baku where he created the newspaper Kavkaz. During the Revolution he was imprisoned and the paper confiscated.

She joined the family of her half sister, Maniounia, in Moscow. Because of the chaotic political situation, they decided to return to Tiflis by train. It was a seemingly endless journey because the trains were repeatedly requisitioned by either the Reds or the Whites. Exhausted passengers were forced off the trains and had to resort to sleeping with their heads on the rails to be sure not to miss incoming trains. When they reached Mykop in the north Caucasus, they decided to rent a house in the countryside to avoid the civil war, but unfortunately their house was precisely on the front lines, and to make things worse, brother Vanya was fighting with the Whites, while brother Kotik was on the Reds’ side.

Helene was deeply devoted to Maniounia and to her nephew, Gary, but she had an ambivalent relationship with her Alsatian brother-in-law, Sacha Moët, who always used to tease her because her skin was so dark. In Mykop Maniounia continued to act and dress like the great aristocrat, even when they were hiding in the cellar from Red army incursions. She had apparently lost touch with the reality she could not cope with. In these dramatic circumstances, Sacha declared his love to Helene, who would never betray her sister, even though she might have been attracted to him. It was at this point that she fled to Europe.

1918 Helene left Russia from Novorossisk on a ship bound for Istanbul. The other passengers looked down on her: at the time no well-bred young girl would ever travel alone – even during a revolution! She then embarked on a ship to Marseille, but as she did not have a small pox vaccination certificate, she risked being arrested by the Turkish authorities and ending up in a harem on the Island of Prinkipò. The Italian captain of the ship took pity of her plight and hid her during their inspection.